ТУР ИМАННА

«Тур иманна» переводится с эвенского как «Земля снега».

Через метод глубинных интервью художница зафиксировала важность долгой зимы для поддержания образа жизни, связанного с традиционными для коренных народов Камчатки промыслами.

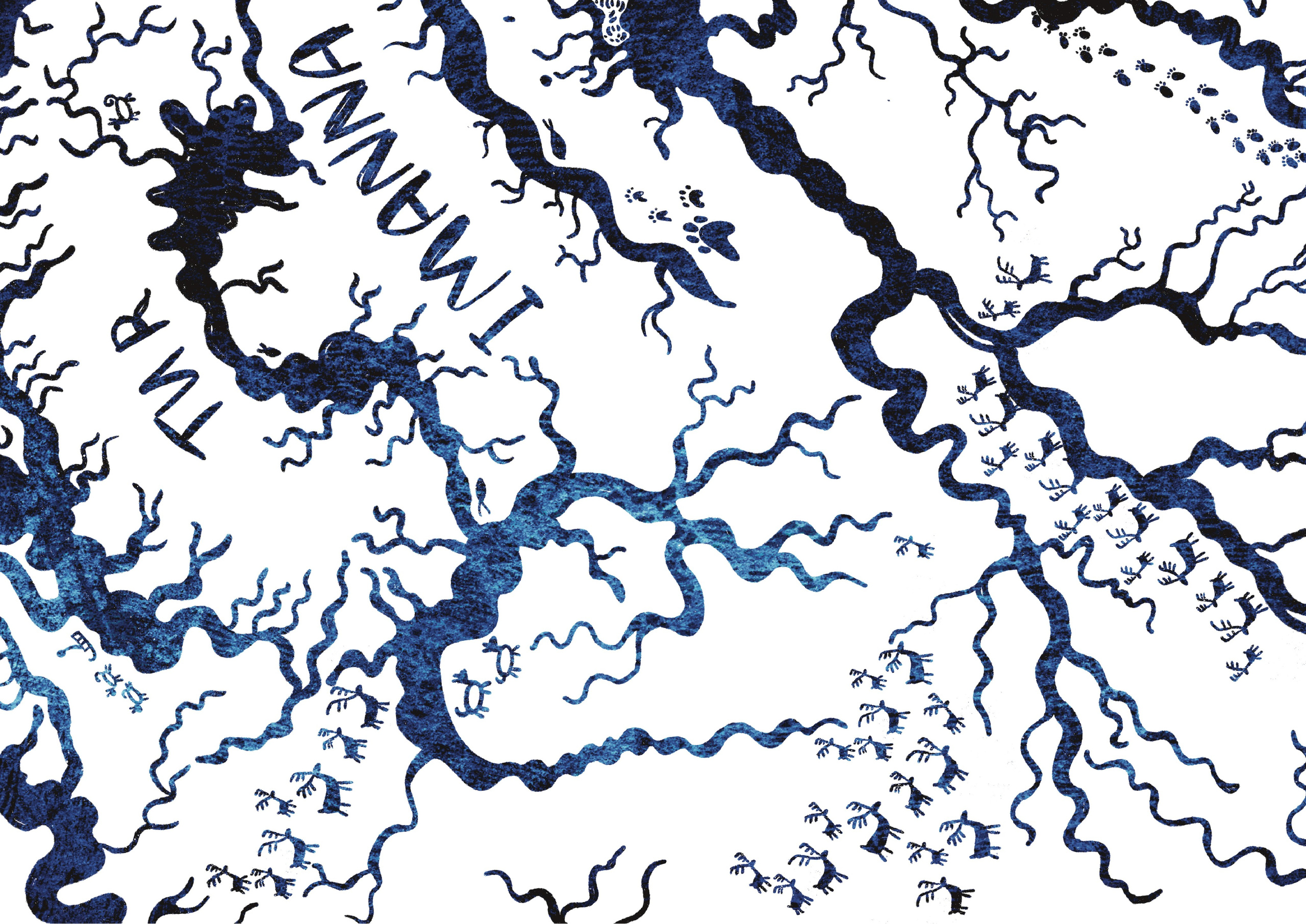

Графические работы, выполненные для проекта «Тур иманна» отображают важные для культурного контекста Камчатского полуострова образы: ворона по имени Кутх, по легенде создавшего полуостров своей слезой; ездовых собак, особо ценных для жителей северных поселкв как единственное средство передвижения зимой; оленей, чей ритм жизни тотально подчиняет себе оленеводов и проч.

В зине использованы цитаты из интервью жителя центральной Камчатки, шестидесятилетнего художника-костореза, мастера по созданию бубнов и нарт, охотника и участника гонок на собачьих упряжках «Берингия», Андрея Адуканова.

Проект был экспонирован на «Frozen matters», галерея Siggeruds, Норвегия, Будё, 2024

Я объездил всю Камчатку. На собачьих упряжках был на северах, даже на Чукотку заезжали. Через все северные города: Оссору, Тымлат, Тиличики, Слаутное и другие ходили вместе с Берингией (традиционные гонки на собачьих упряжках), я и нарты для участников делал и как волонтер ездил помогал. Берингия — это один раз и навсегда. Север, просторы, собаки, азарт. Люди зимой здесь счастливы. У них коньки, всю зиму катаются, запасают юколу — сушеную красную рыбу и питаются зимой, отправляют ее детям в Москву и Питер. С Беренгией нас встречали как праздник в каждом поселке, кормили пирогами. Людей там защищает зима, консервирует их доброту и открытость.

Северные поселки малолюдные — после отмены экспорта оленины с Камчатки (при Горбачеве) содержать стадо стало дорого, люди спивались и совершали самоубийства, потому что не знали, как жить без оленей. Там, где раньше жило 10000 человек, сейчас живет 400. И оленеводов сейчас на Камчатке — по пальцам рук пересчитать всех можно.

Олени — это стиль жизни. Они не будут дважды есть на одном месте — чистые животные, чистоту любят. Им нужны новые пастбища, вот и нужно с ними ходить, кочевать. А коряков, которые оседлые, без оленей, имеющие хозяйство, мы называем кисляки между собой, потому что едят кислое мясо, не выгуленное в горах камчатских.

Мои родители были оленеводами, все время кочевали. Меня поэтому и отдали в интернат, чтоб учился, но я все равно им помогал на каникулах. Поэтому я так хорошо на русском говорю, хотя у нас в семье говорили только на корякском и на эвенском — оленеводы люди необщительные. Они вместе с оленями ходят по просторам своего края и чувствуют себя свободными. И не нужен им город.

В Анавгае долго жил, преподавал резьбу по кости, женился там, два сына у меня, один тоже режет и бубны мне делать помогает. Сейчас живу в Эссо, здесь и за мамой сейчас ухаживаю. Летом в Мильково работаю, а все остальное время в Эссо живу, езжу на снегоходе зимой заготавливать каменную березу для бубнов, зимнюю рыбалку люблю.

Здесь зима долгая, не то что на материке.

Камчатка — это одно большое сердце, снежное и горячее, как вулкан зимой.

2024